New school, new luck

Wenn es eng wird im eigenen Haus, weil die Familie wächst, ist es Zeit für einen Wohnungswechsel. Besteht gar die Möglichkeit für einen Neubau, umso besser, lassen sich doch so...

YOUR FORUM FOR PLAY, SPORTS UND LEISURE AREAS

Physical Activity as an Environmental Health Problem.

The World Health Organization observed more than a three-fold increase in global obesity rates since 1975 and major public health organizations have begun to recognize childhood obesity “as one of the most serious public health challenges in the 21st century”. In 2015-2016, the overall crude prevalence of obesity was 39.8% among adults and 18.5% among youth in the United States. The rise in obesity has major implications for the future of health because obesity is associated with a variety of health risks including cancer, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, among others.

The fundamental cause of obesity is an imbalance of calorie intake (diet) and calorie expenditure (physical activity). Policymakers have genuinely struggled to identify clear solutions for addressing the obesity epidemic. One path for intervention is through the creation of leptogenic environments that encourage physical activity through careful design practice. A large body of literature has emerged over the last two decades to examine correlates between various facets of the built environment, such as transportation structure and connectivity, land use mix, and access to recreational services and other green spaces. While this work shows that there is some relation between urban environments and physical activity behavior, the results are decidedly mixed, due in part to the difficulties of teasing apart the effects of specific facets of the environment from a host of social, cultural, and economic factors.

One promising approach is to study the design impacts of highly controlled environments, where the behavioral effects in response to changes in the environment can be systematically observed. Children are often a key public health target for intervention because obesity early in life is a strong predictor of obesity in adulthood. Indeed, one of the greatest opportunities for impactful, targeted interventions to improve physical activity behavior may exist with schools. Physical activity confers numerous additional health benefits to children throughout their lives, including reduced rates of cardiovascular disease, reduced risk for diabetes, and improved cognitive development and brain function. Elementary school playgrounds (schoolyards) offer an important and focused opportunity to explore the relation between landscape design and physical activity. The average child in the United States spends over 1000 hours in school each year, where they are consistently provided with a time to utilize the schoolyards for unstructured play, which may comprise around a sixth of children’s daily physical activity in the US.

The Learning Landscapes Program

Between 1998 and 2013, the city of Denver began performing renovations to the 98 elementary schoolyards in the city which were on average 50 years old. The renovation was eventually incorporated into an initiative called “Learning Landscapes,” born out of a partnership between the University of Colorado and the city of Denver. The playground designs were produced by students of landscape architecture at the university in close collaboration with community groups, who participated in the design of the schoolyards through focus groups and public meetings. The goals of the project were to transform schoolyard spaces “into attractive and safe multiuse schoolyards tailored to the needs and desires of the local community, creating fun, participatory play areas that encourage outdoor play and learning, improve opportunities for physical activity for children of all ages, and ‘‘green’’ the grounds.”. Elements of the schoolyards included public art, banners, sports activity areas, gardens, and modern play equipment. The “open spaces” around the schools were renovated to provide spaces for children to practice organized sports, such as soccer or baseball, in addition to spaces on paved surfaces for sports such as basketball or handball.

The National Institutes of Health funded an interdisciplinary team of researchers from exercise science, health education, public health, landscape architecture, and medical geography to explore the impacts of the work on children’s behavioral health. Renovation spanned multiple decades, with some schools receiving renovation earlier than others, yielding an opportunity to perform a naturalistic experiment. Research team members worked closely with the district and school principals to organize systematic observations of physical activity on both renovated and unrenovated schoolgrounds, matched by the ethnicity and income of the school populations. Twelve schools were observed as controls without renovated playgrounds, and another twelve as the intervention group with renovation from the previous five years.

The “System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth” (SOPLAY), was used to record physical activity behavior by children at all participating schools. During recess, observers counted the number of children in zones across the schoolyards, noting the children’s gender and physical activity status (whether sedentary, moderately active, or vigorously active). Because the observations were collected in observational zones—numerated and designated areas of the schoolyard designed to facilitate observation—the team was also able to map activity within schoolyards, which enabled analysis of which parts of the schoolyards attracted children and where they were most likely to exert moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).

Insights from Research on Playground Renovation and Design Practices

The first question investigated was whether the Learning Landscapes program impacted physical activity behavior. The team employed two primary outcomes to test differences in behavior: (1) the utilization of the schoolyards, or the number of children observed in the space and (2) the rate of MVPA, whether the children engaged in healthy physical activity once they were on the schoolyards.

After first accounting for differences in the schools’ enrollments, the team observed more children utilizing the spaces in schools with renovated schoolyards than in the schools without it. Notably, this effect extended to “optional periods,” beyond the scheduled school day, including time before the beginning of school, after school, and on the weekends, which suggests that the renovation could affect health behavior beyond the context of school recess. One notable finding from an initial analysis showed that the recency of construction played a role; the greatest difference was observed in schools with construction a year or less prior to the observation, suggesting that children may be drawn to the novelty of the newly constructed spaces. This finding was consistent with other work on schoolyard renovation, but it was not clear how long this “recency effect” lasted. There was, however, no statistically detectable difference in the rate of physical activity; children in renovated spaces were as likely to engage in physical activity as children in non-renovated spaces.

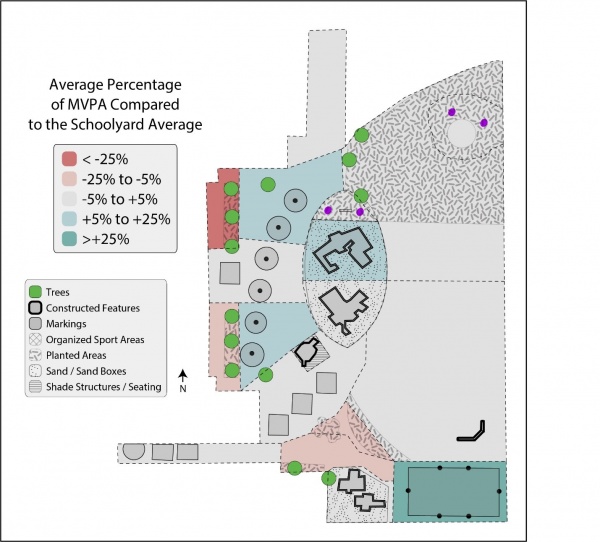

The practice of mapping out zones within the schoolyards enabled analysis of utilization and physical activity patterns within the grounds. Observed counts of children, their gender, and their physical activity status were aggregated into the observation zones for the entire study. Because the school’s playground population was dynamic, constantly changing as a function of what was going on at the school and which student groups had recess at the time of the observations, it was important to carefully standardize counts to show the populations of each zone relative to the schoolyard population in order to effectively estimate utilization. Because the observation zones were different sizes, we also adjusted for the physical area of the zones. Physical activity behavior was calculated by simply dividing the number of children engaged in MVPA by the total number of children observed.

In one analysis, we examined which types of zones experienced the greatest utilization and the highest rates of physical activity, which yielded insight to how children interact with the features of the schoolyards. Children utilized some parts of the grounds more heavily than others; they were particularly concentrated around hard-surface play areas and parts of the schoolyard with playground equipment, for example, and were less concentrated in open fields. Children were observed to be more active in zones with play equipment and markings for organized sports, such as basketball and tetherball. The same analysis also suggested differences in behavior across gender. Boys were more active than girls in play field and basketball areas, while they were higher for girls in areas with playground equipment. In a related analysis, the team analyzed a count of the feature density, the number of constructed features per unit of area, to observe an association between feature density and physical activity rates. Children were more active in zones with a high density of constructed features.

Implications and Future Work

While this work did not demonstrate that schoolyard renovations are an effective tool for physical activity interventions among children, we were able to observe patterns and differences in behavior by examining behavior within schoolyards. One of the primary goals of this research was to produce “scholarship of translation” – research that leads to practical insights around the design considerations of schoolyards. If we mean to develop “healthy spaces” for children, we should demonstrate what kinds of spaces and design practices indeed lead to healthy behavior. This research provides some initial evidence to planners, who may incorporate appropriate design elements. This work might also shed some insight on how educators can best utilize the spaces in their schoolgrounds to encourage more physical activity. We consistently observed that open fields were underutilized and were not associated with high rates of MVPA, for example. This could indicate that children might benefit from guidance or encouragement about how to use open fields for active play, perhaps by providing curricular organization during recess or improved access to equipment, such as soccer balls.

The research team is working with the collected data to continue to study the relationship between children’s environments and their physical activity behavior. These initial analyses only accounted for crude measures of the schoolyard design by examining feature density and the basic type of zone. To advance this work, the team digitized the features of the school into a geographic information system (GIS) in order to produce “activity” maps of the schoolyards to visually display the concentration of activity, overlaid upon a map of the schoolyard’s features. To account for the fact that the activity levels at different schools could vary as a function of the social and cultural influences in the school (such as the income of its student body or its culture), the rates were translated into relative figures that shows the difference in each zone’s activity rate compared to the overall rate for the school as whole. The picture shows an example of an activity map of a schoolyard in the study. The blue shaded zones represent parts of the schoolyard with high rates of MVPA and the red zones are areas where physical activity was low.

There is a great deal of potential for new technologies and additional research to improve our understanding of how children use physical activity spaces during recess. Research from Scandinavian countries has combined global positioning trackers (GPS) with accelerometer data on playgrounds. Fjortøft et al., for example, analyzed a schoolyard in Norway to determine that handball courts produced the most vigorous physical activity Using similar methods, Anderson et al. were able to identify activity hotspots on schoolyards in Denmark to conclude that playground renovation is best served by including a diversity of features. Research examining individual differences in addition to gender, such as age and ethnicity, as well as environmental facets of schoolyards—such as the impact of size and climate - could yield additional, actionable insight to schoolyard design.